MODERN LOVE: FALLING FOR SPACE TECH

FULL CYCLE BIOPLASTICS, MEDIUM, MAY 24, 2021

BY DELAINE MAYER

My image of space tech changed when I laid eyes on Bob and Doug. They were the sleekest American-boy sci-fi duo I’d ever seen. Impeccable space suits, helmets shined to perfection, visors which caught the reflection of a light that framed their faces in space hero glory. If Doug is smirking in this picture like I think he is, it’s because he knew how cool he looked.

They were otherworldly.

Astronauts Doug Hurley, left, and Bob Behnken (SpaceX)

On May 27, 2020, when my world had shrunk down to the size of a Brooklyn apartment which I shared with 3 roommates, when external stimulation was replaced with Zoom and Netflix, when anxiety arrived whispering “I’m the new normal,” when a world of expansiveness had been replaced with limitation, I watched on my computer while Bob and Doug boarded a rocket. I had never seen people board a rocket before. They entered a SpaceX capsule so crisp and modern, it looked like a car ad. By this time, I had spent months watching tv that overnight had become no longer representative of reality (people without masks hanging out in big groups having social experiences — who were they?) And then there were Bob and Doug in real time, doing something cool. Life was happening outside my apartment, to my surprise.

It was hard to believe this was a crewed capsule going to space. This was not my parents’ and grandparents’ version of technology, nor the version of Apollo-era space tech I recalled from childhood movies like October Sky and Apollo 13. Bob and Doug’s technology is for my generation. The astronaut transfer van, a specialized motorhome, had been replaced by a Tesla. The clunky knobs, dials, and switches of old instrument panels were now touchscreens. Watching Bob and Doug inside the capsule offered a glimpse of ambition, science, and optimism happening out in the world, a place I felt I didn’t know anymore, a place I mistakenly thought had shrunk. Amidst that dreary spring lockdown, the launch gave me something to think about beyond my cramped walls — it gave me hope.

The May 27 launch had to be rescheduled due to weather, but even as they were calling it off that day, I knew I was hooked. I’d watched three hours of press on Launch America, including an interview with Elon Musk and then-NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine talking about how important it was to make space cool again, that it was essential for young people to watch rocket launches and find inspiration, to imagine themselves as astronauts setting out for unthinkable destinations.

On May 30, the day Bob and Doug would launch, they rolled up to NASA’s historic Launch Pad 39-A in a falcon-winged white Tesla Model X with the NASA logo (the “NASA meatball”) slapped to the front door. They looked like intergalactic movie stars; their premiere was the start of the commercial space era, kicking off on an American-made rocket from American-soil with a reusable booster that would land on drone ship Of Course I Still Love You, defying the status quo of rocket launches of the last fifty years.

That May 30th afternoon, I sat in the apartment of a potential new boyfriend (so far so good, a year later), hands over my mouth, eyes wide, maybe a little teary depending on who you ask (not me.)

Off Earth, Bob and Doug ushered in a new era of space commercialization while a toy dinosaur, selected by their children, floated in the capsule with them to demonstrate their new weightlessness, their new freedom.

Bob and Tremor, the sparkly “stowaway” Apatosaurus (Screenshot of NASA Video)

Embedded in the DNA of a rocket launch is ambition, adventurism, and opportunity. Bob and Doug’s successful launch and docking with the International Space Station made me feel inspired and optimistic; I hadn’t felt that way in a while.

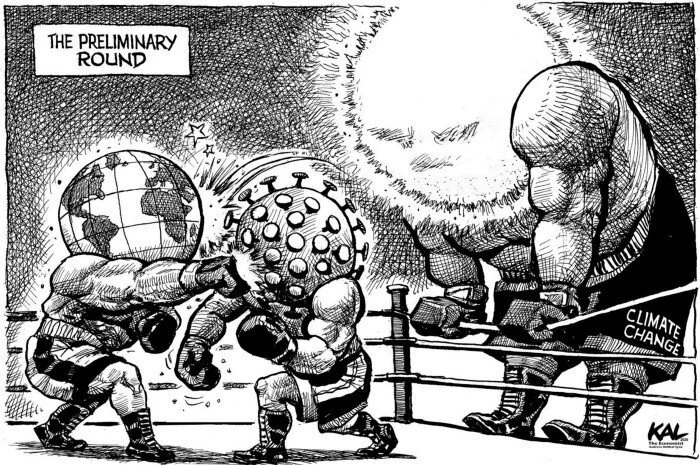

On Earth, things were different. New York City was going into its third month of the Covid-19 lockdown while outrage and protests against police brutality and racial inequity were beginning to unfold. As Anthropause-era “the Earth is healing, we are the virus” memes flooded my social media, climate change, ever the looming existential terror, sat ominously on the sidelines, waiting for its turn in the ring.

The memes were fun, but the reality was terrifying — here is another battle we are unprepared to fight which will require a shift in the global economy, incredible spending, and deep political resolve in order for us to mitigate and adapt. Like with Covid, climate change will impact those most vulnerable and disadvantaged, widening the gap between the global rich and poor, the decision-makers and the decisions-made-for.

Kal, Climate Change V.S. Covid (The Economist)

In my journal on May 27 before Bob and Doug’s first scheduled launch, I wrote, “Both of these truths — that things are terrible, and incredible new things can happen if we care and try — coexist. What does it mean for so many truths to make up one reality? For anger and joy to coexist in the same world, even the same moment, and how do I give each the space and time within me to occupy?”

Today, that answer comes from my work with Full Cycle Bioplastics, a California biotech company whose technology turns organic waste into a non-toxic, compostable plastic alternative called Polyhydroxyalkanoate, or PHA. I work with R&D and the Growth teams to scale-up processes and best practices that support commercialization. In my R&D-Growth meetings, the tagline has become “where possibility meets reality,” where our expansive visions and inherent optimism get loving reality checks. The truth is, we’re still a start-up, we’re still growing, we don’t have all the answers, but we’re working hard to get there because we know the climate crisis requires a myriad of solutions, and we’re pretty sure we have a great one.

On my Dream Big days, I mentally open Google Earth and imagine the planet covered in pins marking Full Cycle facilities that are turning food waste into bioplastic, avoiding landfilling of methane- and carbon-emitting wastes and displacing oil-based plastics all over the world. The unfathomable stream of trash currently entering our waterways and oceans dries up as we advance truly circular solutions.

It’s good to dream big like this. “Impossible” dreams provide aim, focus.

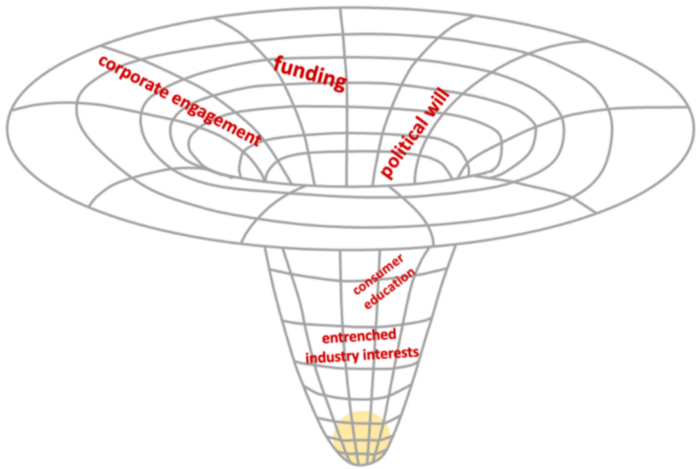

For rocket scientists, the hardest part about space is getting there, getting out of the deep gravity well of Earth. A rocket scientist’s impossible dreams involve orbital mechanics, physics, and the tyranny of the rocket equation.

“A gravity well represents the gravitational field of an object. The more massive the object, the deeper the well. For example, the Earth is much more massive than the Moon and so has a deeper gravity well or a stronger gravitational field.” (St. Mary’s University)

For environmental scientists, climate technologists, and conservationists, our impossible dreams have been political will, consumer education, corporate engagement, and upending entrenched industry interests — facing a challenge as big, costly, and complex as climate change has been a gravity well of its own. It keeps us locked in old ways of thinking, doing, and making.

The Gravity Well of Climate Change Inaction (Modified image from St. Mary’s University)

And yet, the momentum is growing for our own moonshot, our climate change Earthshot. We, too, can overcome the climate change gravity well and break free from the outdated 20th century economic mindset of Take-Make-Waste. This linear way of thinking doesn’t work. Take-Make-Waste leaves the planet with exposed and vulnerable sites of raw material extraction (take), inefficient and inhumane systems of production (make), and pollution that impacts our oceans, atmosphere, and our health (waste.) We have the technology, political will, and growing environmental education to develop and economically progress in a different way. We can be the Bob and Dougs of a circular economy, but we’ve got to get on a different kind of rocket first and leave the old technology behind.

—

Three months into my working at Full Cycle, Jeff Anderson, Co-CEO and Co-Founder, forwarded the Growth team an email about a “NASA opportunity for sustainable tech” with a one-lined message: “Space-age packaging.”

This kicked off our application and acceptance to the March 2021 NASA iTech Ignite the Night Semifinalist round. During the live virtual competition, our pitch video was played and Dane Anderson, Co-CEO and Co-Founder, and I participated in a live round of Q&A with NASA’s Chief Technologists. We argued for the need for circular product development on Earth, made possible with Full Cycle’s waste-to-biopolymer PHA, while affirming that PHA has the potential to enable circular design in space, too. NASA’s Chief Technologists agreed.

The win attested to Dane and Jeff’s years of work in advancing a technology that, at the time they were developing it in the early 2010s, had limited market traction and a niche audience. Personally, the win happened a year to the day after unexpectedly being forced to face a painful break-up as NYC went into lockdown (apparently that relationship had limited traction, too.) And yet here we all were, Full Cycle and I, marking the passage of a decade and a year respectively, with new teams building out promising futures together, both professionally and personally. That, too, had seemed impossible at times.

March 2021 NASA iTech Ignite the Night Winners!

On May 27, 2021 one year after Bob and Doug’s first attempt to get to the International Space Station, Full Cycle will enter NASA iTech’s 2021 Forum as a finalist, reaffirming our commitment to solving big challenges and doing believed-to-be-impossible things.

The Forum highlights finalists “whose innovations show the greatest potential for commercialization and solutions to problems in space and here on Earth.” NASA’s Center Chief Technologists selected the finalists and will judge the event, including pitches, thematic discussions, and impact tables.

Full Cycle is interested in supporting Artemis and Gateway, as well as replacing plastics in NASA’s terrestrial supply chain. Anaerobic digestion offers potential for waste management, fuel generation, and manufacturing in space, all of which are solutions that NASA and commercial space players seek as they plan the development of long-term lunar and Martian settlements. These are also solutions that we know work on Earth to solve these same challenges.

The International Space Station over the Western Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau (NASA, 2011)

“The overview effect [is what] astronauts typically achieve when they accomplish their first spaceflight and look back at the Earth and realize that there are no boundaries or borders really observable from space,” Astronaut Bob told CNBC. “You see that it’s a single planet with a shared atmosphere. It’s our shared place in this universe. So I think that perspective, as we go through things like the pandemic or we see the challenges across our nation or across the world, we recognize that we all face them together.”

This isn’t just “new packaging” or “space-age packaging” that Full Cycle is advancing. There is a new era unfolding that we’re a part of, rooted in circular economy principles, forcing us to reexamine our relationships with one another, our planet, and the space around and between us. Doing things because that’s the way it’s been done simply doesn’t cut it — that’s the 20th century gravity well holding us back. It’s time to break out.

KEYWORDS: NASA; SPACEX; FULL CYCLE BIOPLASTICS; SPACE TECHNOLOGY; CIRCULAR ECONOMY; PHA; POLYHYDROXYALKANOATE; BIOPLASTICS